Crafted and Conniving

By Remy Haynes

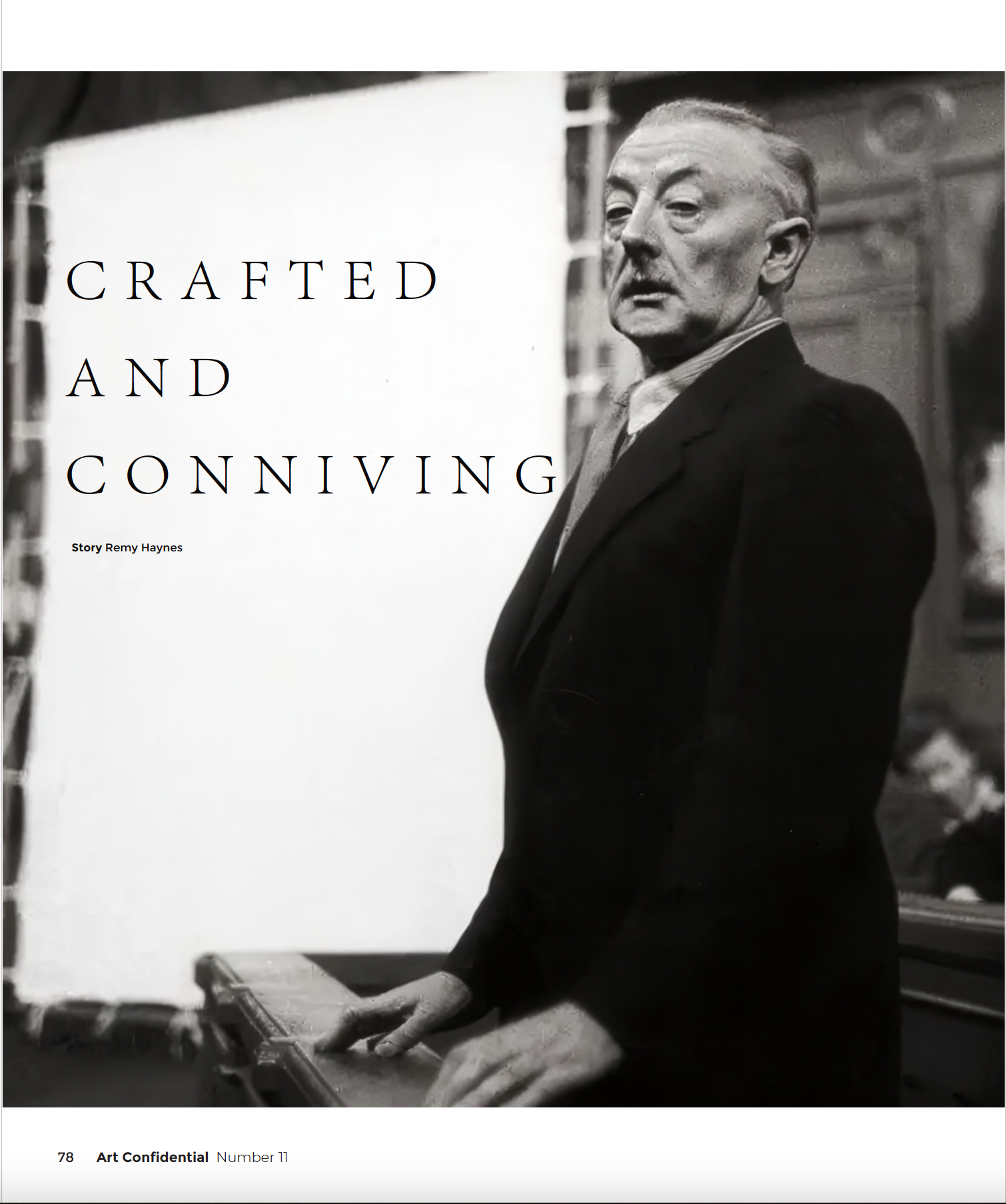

One of the most problematic periods in art history is undoubtedly 1933 to 1945, the years of the European Nazi regime. During this era, countless artworks were destroyed or forcibly purchased, often from Jewish owners. As a result, it is crucial for the art market to thoroughly understand the origin of artworks from this time, to avoid selling potentially stolen pieces. This issue is further complicated by the presence of fake artworks, created to deceive, and sold to the Nazi leadership. A notorious example of this is Han van Meegeren's actions in one of the 20th century's most infamous cases of art forgery.

Henricus ‘Han’ van Meegeren was born in the Netherlands in 1889. After an unsuccessful attempt at studying architecture, he decided to pursue his passion for painting and drawing. In his early, legitimate career, Van Meegeren painted portraits and produced copies of works by Dutch Old Masters, such as Frans Hals. Han attempted to make a career as an artist, but art critics dismissed his work.

In response to this lukewarm reception, Van Meegeren stopped copying Old Masters and began creating new works that mimicked their style as convincingly as possible.

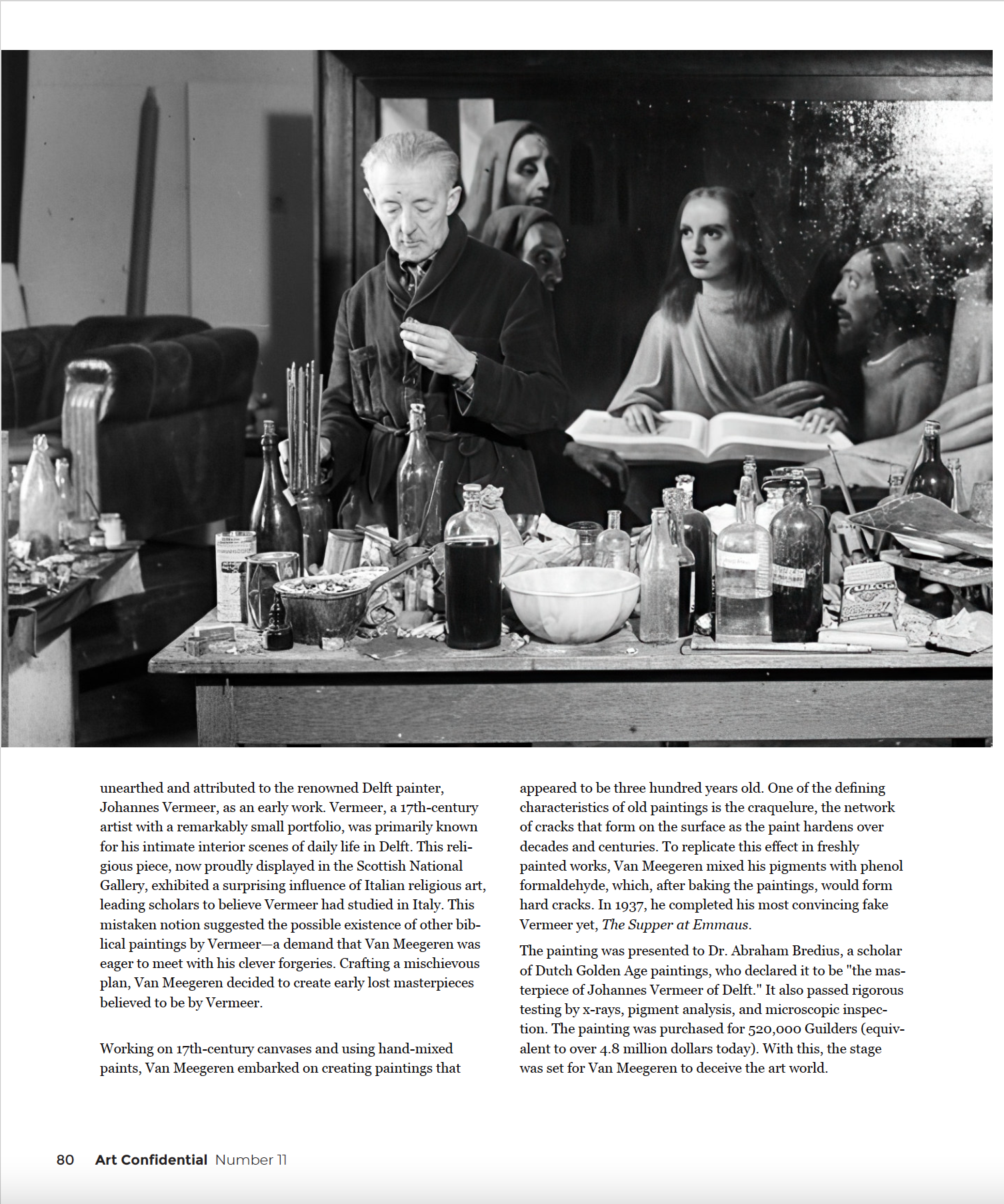

In 1901, a large and audaciously painted religious composition titled "Christ in the House of Martha and Mary" was unearthed and misattributed to famous Delft painter, Johannes Vermeer as an early work. Vermeer was a 17th-century painter but with a shockingly small portfolio, mainly depicting cozy interior scenes of daily life in Delft. This religious piece, now proudly displayed in the Scottish National Gallery, showed a surprising influence of Italian religious art, leading scholars to mistakenly believe Vermeer had studied in Italy. This notion hinted at the existence of many more biblical paintings by Vermeer, to which Van Meegeren was ready to meet the demand, with his clever forgeries. Van Meegeren concocted a mischievous plan. He decided to craft supposedly lost early masterpieces of Vermeer.

Working on 17th-century canvases and using hand mixed paints, Van Meegeren set about creating paintings that looked three hundred years old. One of the main characteristics of old paintings are cracks in the picture surface that appear as the paint hardens over decades and centuries, otherwise known as ‘craquelure.’ To achieve this effect in freshly painted works, Van Meegeren mixed his pigments with phenol formaldehyde which, after he baked his paintings, would form hard cracks. In 1937, he completed his best fake Vermeer yet, ‘The Supper at Emmaus.’

The picture was shown to Dr. Abraham Bredius, scholar of Dutch Golden Age paintings, who declared the painting to be ‘the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft.’ It also passed satisfactory testing by x-rays, pigment analysis, and inspection under a microscope. The picture was bought for 520,000 Guilders (equivalent to over 4.8 million dollars today). The scene was set for Van Meegeren to deceive the art world…

Now a wealthy man, Van Meegeren continued to produce fake early Vermeers, including a monumental Last Supper, as well as forgeries of other artists such as Pieter de Hooch. With the Second World War and its accompanying Nazi occupation came opportunity for Van Meegeren, who sold another of his creations, ‘Christ with the Adultress,’ to a Nazi art dealer, Alois Miedl. Miedl was a Dutch citizen who made a career of forcibly buying, or looting, Jewish-owned artworks and then selling them to the occupying forces. Miedl eventually sold the supposed Vermeer masterpiece to one of the most prolific of Nazi looters, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring, who apparently gave Miedl 137 stolen pictures in return for the piece. This painting eventually would lead to Van Meegeren’s demise.

When ‘Last Supper’ was discovered in an Austrian salt mine by the American Army in 1945, a paper trail led back to Van Meegeren. The forger was finally arrested and charged with aiding and abetting the enemy, a crime that carried with it the death penalty. His only way out of such a sentence was to confess to the forgery. He also found himself facing charges of fraud and forgery for the works he sold before the War, many of which had ended up in state museums. The discovery that he had used Bakelite, to age his paintings confirmed his guilt and he was sentenced to only one year in prison.

Van Meegeren suffered a heart attack in 1947, shortly before he was due to be imprisoned. His downfall gave him not only incredible fame, but also popularity. The fact that he had knowingly committed fraud, even against the Dutch state, was apparently unimportant when compared to his reputation for fooling the despised Göring. Indeed, a 1947 poll named the forger the second most popular Dutchman, after the prime minister. You can even watch a movie today about Van Meegeren’s forgeries on Netflix called, ‘The Last Vermeer,’ starring Guy Ritchie.

This extraordinary case highlights the dangers of forgery in the art market. Museums must carry out far greater due diligence when it comes to technical analysis of artowrk. In the realm of Old Master art dealing, the question of authorship holds utmost significance. Unlike most modern and contemporary artworks, which clearly identify the artist in question, the authorship of Old Master paintings is a bit more complicated. There are many copies of old works, some that are signed and some that are not. Consequently, attributing Old Master paintings is a meticulous process that entails many scientific steps.

So, had these checks been done correctly in the 1930s and 40s, it would not have taken long to determine that Van Meegeren’s paintings were forgeries. The Second World War removed the resources needed for such research to take place and left the door open for people who wanted to exploit the system. The infamous forgeries of Han Van Meegeren are a rare example of an individual who profited from Nazi intervention in the art market and the war that distracted many. So, was Van Meegeren lucky, smart, conniving or just an artist trying to pay his rent? You’ll have to watch the movie to judge for yourself.